In the late 1800s, women reporters were rare. Even if a newspaper had a female reporter on staff, she would often be given assignments labeled “women’s interests”–such as fashion, gardening, or social events. Nellie Bly was not such a woman. She was fearless in her reporting and pushed to write impactful stories. Bly’s innovative investigative approach made her the best-known journalist of her time.

Early Years

Nellie Bly was born Elizabeth Jane Cochran on May 5, 1864, in Cochran’s Mills, Pennsylvania. The town was named after her father who owned the town’s mill and served as a judge. Elizabeth Cochran was one of 15 children. Her father had 10 children with his first wife and 5 children with his second wife, Cochran’s mother. The family lived a comfortable life until, when Elizabeth Cochran was 6, her father died without a will. Her mother remarried for financial stability but divorced several years later due to abuse.

At age 15 with a desire for independence and to help support her family, Cochran enrolled at the Indiana Normal School to become a teacher. After one semester she had to quit school due to lack of tuition money. She then moved to Pittsburgh to live with her mother and brothers. She helped her mother run a boarding house but had difficulty finding other work opportunities.

Becoming Nellie Bly

In 1885, the Pittsburg[h] Dispatch published an article titled “What Girls Are Good For.” It asserted that women should tend children and households. The article also criticized women in the workforce. Cochran, who knew many young women in Pittsburgh who worked to survive, penned a strongly worded yet thoughtful response to the paper. The editor was impressed with her writing skills and hired Cochran as a reporter.

At the Dispatch, her editor assigned her the pen name Nellie Bly, a misspelling of a popular song by Stephen Foster “Nelly Bly.” The misspelling stuck. Bly’s first story told of the difficulties of poor working girls. She also wrote about divorce and harsh working conditions for women factory workers. Factory owners, however, were displeased with Bly’s stories that were critical of business practices. Some advertisers stopped funding the paper. The paper’s editors then gave Bly topics of “women’s interests.” Bly quit in dissatisfaction and moved to New York City.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

In 1887, Bly’s determination led her to the offices of Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. Her first assignment for Pulitzer’s paper was to report on the mental institution on Blackwell’s Island in New York. (Blackwell’s Island is now called Roosevelt Island. It is located on New York City’s East River.) At 23 years old, Bly faked mental illness and was admitted to the institution. For ten days she lived with the other patients, experiencing the same treatment and harsh conditions they did. Her undercover reporting made Bly one of the first investigative journalists.

Bly’s six-part series, Ten Days in the Mad-House, exposed cruel beatings, ice cold baths, forced meals, and more. Her story shocked the public. After further investigations, funding was increased for the institution and patient care improved.

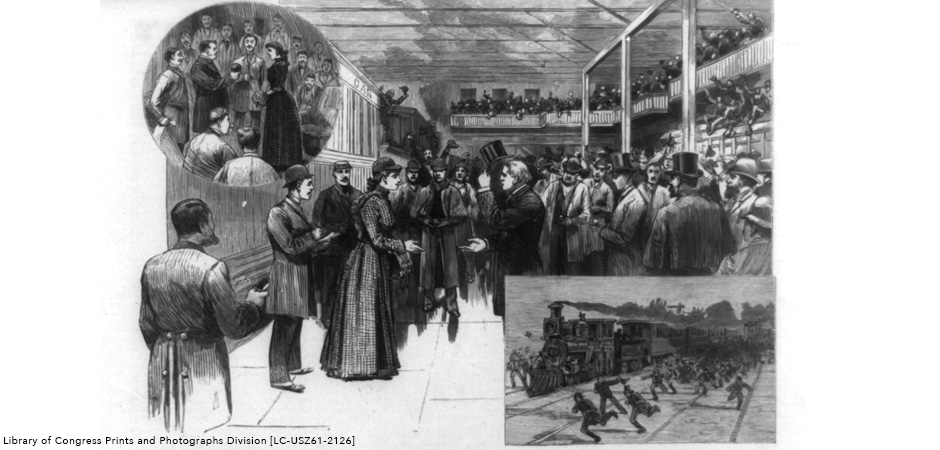

Bly continued to report the stories of the poor and powerless for the New York World. She exposed corruption in government, poor treatment of women prisoners by police, and theft of immigrants by an employment agency. In 1894, while reporting on the Pullman Strike in Chicago, Bly covered the strike from the perspective of the striking railroad workers. She was the only reporter to do so.

Trip Around the World

Bly is also remembered for her trip around the world in 1889. After reading Jules Verne’s popular book Around the World in 80 Days, Bly decided to see how long it would take her to travel around the world. The New York World hooked readers by publishing daily updates on Bly’s travels and running a contest to guess her travel time. The newspaper documented her journey by ship, train, and horse. Bly set a record by finishing the trip in 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes, and 14 seconds.

Businesswoman

At age 30, Bly retired from journalism and married industrialist Robert Seamen. When he died 10 years later, Bly ran his Iron Clad Manufacturing Company. Ultimately, the company went bankrupt due to employee fraud.

Bly returned to her work as a journalist. She covered women suffrage stories and traveled to Europe to report on World War I. During the war, she became the first woman to report from the trenches on the front line. Bly was reporting for the New York Journal when she developed pneumonia and died on January 27, 1922.