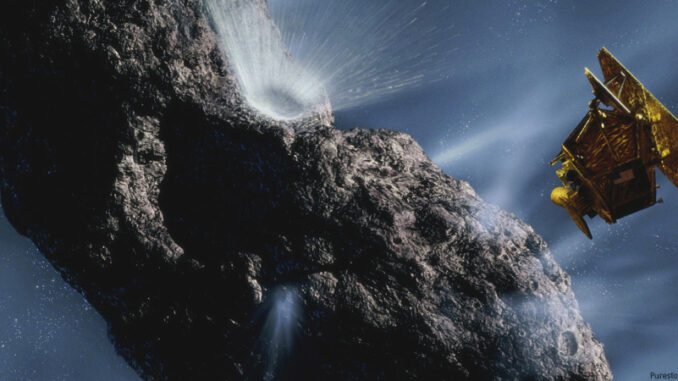

The European Space Agency (ESA), Europe’s equivalent of our NASA, successfully landed the first probe ever on a comet on November 12. Mission control is located at the European Space Operations Centre located in Darmstadt, Germany.

The Mission

Ten years ago, ESA launched a robotic space probe called Rosetta into space. Its original target was a comet called Wirtanen. But a delay made them lose their window of opportunity to successfully reach it. So they reassessed and chose another, called Churyumov-Gerasimenko, also known as 67P. (Comets were once named for the person(s) who discovered them. Since 1994, they are given a numeral followed by letter as established by the international Astronomical Union).

Aboard Rosetta was a 220-pound piece of robotic machinery called the Philae (named after an ancient Egyptian obelisk monument). Philae was designed to detach from the spacecraft and land directly onto the comet. One of the biggest challenges of landing on 67P was its almost complete lack of gravity. Another was not being able to determine the condition and make-up of the surface of the comet. Not knowing if the ground would hard or soft, icy, rocky or dusty made preparing touchdown difficult. Engineers installed a harpoon system that would have anchored Philae to the ground. But it did not work. When the lander finally did make contact, it initially bounced nearly half a mile back up into space.

Why Comets?

When you think “space exploration,” images of planets and moons probably come to mind. But comets, sometimes called “dirty snowballs” because they are largely made up of rock particles and ice, are said to contain the most primitive material in the solar system. Some researchers believe comets were responsible for bringing water to earth billions of years ago.

By studying comets, scientists can get a better understanding of the earliest formation of our solar system. In addition, they contain a potentially rich resource of water, liquid hydrogen and oxygen. These could potentially be used as fueling stations and “watering holes” for spacecraft exploring the further reaches of space.

Philae’s Goals

The lander finally came to rest on Churyumov-Gerasimenko and successfully transmitted data back to Rosetta. Philae contained a battery pack that allowed it to run for 60 hours, collecting data. The team at ESA is currently analyzing that information. The instruments were created to measure the following types of information: the chemical composition of the comet, the temperature and electrical properties of its surface, and the gas and dust that surrounds it and make up its “tail.” Additionally, one of the sensors was equipped with a hammer designed to break through the comet’s crust. After failing at its task, the hammer broke. Researchers were also hoping that solar power (as the comet approached the sun) would have increased the life of the battery pack, but that didn’t happen. Despite these setbacks, the Rosetta mission was considered a success.