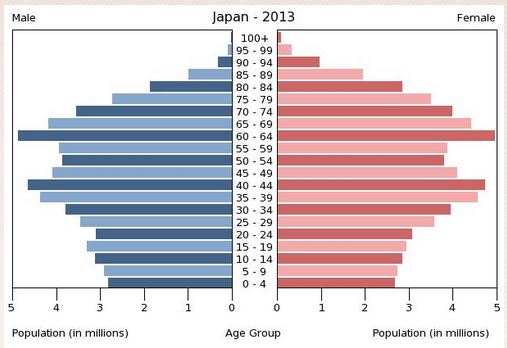

The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Japan recently reported that there were 6,000 fewer babies born in 2013 (1,031,000 total) than the year before. This is the fifth consecutive period of decrease. At the same time, there were 19,000 more deaths (1,275,000). This trend is not new news, as Japan has seen a decline in its population for the several years. A special committee called the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research conducts a 50-year demographic forecast every five years. With a median age of 46, Japan is predicted to lose one-third of its residents in the next 50 years.

What is Happening

Like other parts of the world, lowering populations are being caused by a combination of lowered birth rates and an increase in life expectancy. In Japan, the phenomenon (known as koreikashakai) is happening at a faster rate than anywhere else in the world. 25 percent of Japan’s population is now over the age of 65. In comparison, only 14 percent of Americans are in this age group, and this is considered high, with the Baby Boomers demographic reaching advanced age.

Both young men and women in the country are planning family growth more carefully and are, in general, waiting longer to have families. Those families who do have children are having fewer of them, with an average of 1.5 children per woman, than previous generations. Other countries with similar “voluntary mass childlessness” compensate the lower birth rate with immigration. Japan does not. Some theorize that the lower immigration rate is because Japanese is a difficult language to learn to speak and to write. Others believe it is because of a long-standing fear of change and non-Japanese residents.

Another factor in the imbalance between the generations is that life-expectancy in Japan is also one of the highest in the world, increasing from 72 years in 1980 to 82 years in 2010.

Implications

The government spending of any society depends upon the needs of its citizens. A decline in population is likely to lead to a shrinking labor force, which means an increasing tax and economic burden on those of “working age.” In 1970, for every 1 elderly citizen, there were 13.5 citizens of “working age.” By 2030, experts predict this ratio will drop to 1 citizen to 2.1 of working age. While Japan saves money on child care and education, the cost of pensions, healthcare and assisted-living care are expected to become a burden. Japan currently has the world’s third-largest economy behind the U.S. and China.

While this situation is seen by many as a crisis, there are others who believe this trend can create opportunity. For example, many Japanese seniors are considered some of the healthiest in the world. They lead active and productive lives, well after retirement, which allow them to contribute to the society at large and the economy in particular. Those collecting generous retirement pensions are likely to use them to stimulate economic growth. Some argue that fewer people in the future could mean a better quality of life with more living space and less demands on natural resources.

Regardless of opinions, the Japanese government faces significant challenges in adjusting to the reality of a shrinking population.