![Frances Benjamin Johnston (American, 1864-1952); [Carlisle Indian School, Carlisle, Pa. Band posed at the bandstand]; [1901] Carlisle Indian School, Carlisle, Pa. Band posed at the bandstand] 1901](https://mhebtw.mheducation.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/071921_02P_FS-678x381.jpg)

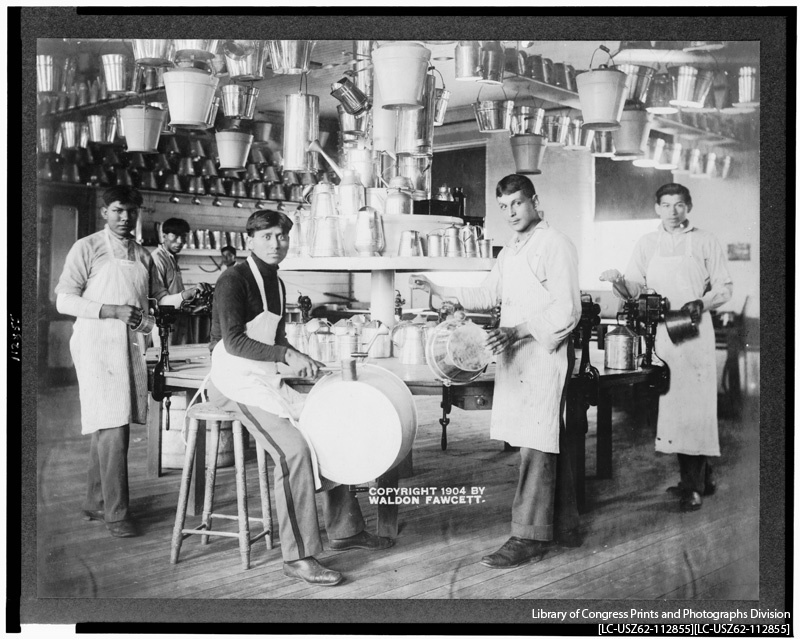

Last month, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland–the first Indigenous person ever to be appointed to this position–announced a federal initiative to formally investigate the history of American Indian boarding schools. Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act of 1819 and continuing through the late 1970s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and various Christian church denominations removed hundreds of thousands of Native American children from their families and sent them to boarding schools in thirty different states. The people leading this effort wanted to teach Native Americans how to live within “white” culture more successfully.

By 1926, almost 83 percent of Native American school-age children attended these schools. Now, the federal government is working to learn more about the experience provided in those school. Current leaders acknowledge that separating Native American children from their family and culture was traumatic to the students. Better understanding the experience may begin to heal the intergenerational trauma that resulted from these historic events.

What Caused This Investigation?

Earlier this summer, the remains of 215 Indigenous children were found at the site of a former boarding school in British Columbia, Canada. Some of those buried were as young as three years old. More than1,000 such burials have been found this summer in Canada alone.

What Happened in Boarding Schools?

Life in the schools was incredibly hard and cruel. Because the schools wanted to mold these students to fit American culture, children were beaten for speaking their native languages. Food deprivation was another common punishment. Native American children’s hair, which often held spiritual significance, was cut upon arrival, and their Native names were replaced with European ones.

Even for those children who survived their time in the schools, the outcome was often traumatic. Many were placed into the foster care system or declared missing and were never returned to their families. Being separated from one’s family caused some Native American children to grow up with social and emotional consequences. Even after the boarding school program ended in 1978, the government often still separated Native children from their families. Many of these separations were the result of drug abuse and addictions that justified removing a new generation of children from their families and culture. But it did not reflect that the parent’s trauma in boarding schools contributed to their problems as parents. A 2012 survey found that Native American children in Maine were five times more likely to be placed into foster care than non-Natives. And a 2019 study found that 70 percent of Cherokee children in the Midwest had been placed into non-Native foster homes.

What Will the Initiative Do?

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative will investigate more than 365 boarding school sites in the United States. This means that officials and experts will look through school attendance records to identify children and their tribal affiliations; consult with various Native and tribal organizations; and issue a final report to Haaland by April 1, 2022.

Why Does It Matter?

According to Haaland, reckoning with the past is a critical first step to healing from it. The Native American population has generations of trauma that they have faced. tBut the physical and emotional health needs of Native Americans are still chronically under addressed. For example, a Native American person only receives 28 percent of the federal healthcare spending that a non-Native person does. It is hoped that the report will provide evidence for the government to allocate a greater share of resources to Native American people in the future.