There is a history of witch hunts that terrorized early modern societies, but those persecuted by these events are often misremembered or forgotten. How did these societies become inflicted with hysteria and what has been done to correct the historical record and obtain justice for the falsely accused?

A Brief History of Witch Hunts

In Christian Europe during medieval times, belief in the supernatural was commonplace. Evil magic was feared and decried by the church. Starting in the 11th century, Christian leaders rejected heretics, those who went against the accepted religious beliefs. Over time, the idea developed that witches were the worst kind of heretic . Accused witches were thought to be consorting with the devil and in need of punishment to keep Christian society safe.

In 1486, Malleus Maleficarum was first published by theologians in Germany. The book elevated witchcraft to the same criminal status of heresy, which was routinely tried in secular courts. The book acted as a manual to recognize witches, conduct trials, and inflict punishment. It argued that the death penalty was the only way to stop witchcraft. The book was used in royal courts during the Renaissance, making witch trials part of the normal operation of the state. This led to increasingly brutal persecutions in the 16th and 17th centuries. Waves of trials sprung up across the continent and affected thousands of people. The accused were investigated based upon circumstantial evidence and some of the accused were tortured. These tactics led to false confessions and the questionable naming of other witches. Groups of these trials occurred in Germany and Switzerland, England and Scotland, France and Belgium, and Scandinavia. Such trials ended in Europe around 1780.

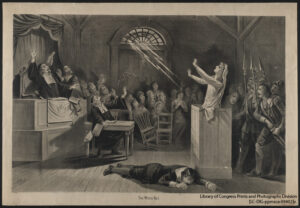

As the witch craze unfolded, women became closely associated with the witch archetype. Women who were childless, husbandless, elderly, or poor were the most likely targets of witch hunts. Those accused of witchcraft were typically on the fringes of society or acted in socially unacceptable ways. Most accusations began due to local neighborhood dramas or gossip which could quickly devolve into trials. Differing by location, various trials led to the persecution of tens, hundreds, or thousands of people. Historians estimate that there were between 40,000 and 50,000 executions, with hundreds of thousands more accused. The witch craze spilled over to the English colonies across the Atlantic Ocean. This caused the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 in colonial Massachusetts. Like in Europe, these trials were stoked by superstition, paranoia, scapegoating, and petty jealousies. In Salem, at least 172 people were accused, with 20 executed.

Correcting the Historical Record

After the Salem trials, some of the accused petitioned to have their convictions overturned. In 1711, 20 people were pardoned and offered retribution. However, out of fear or shame, not all families came forward. In 1957, Massachusetts passed a law to clear the names of all remaining people affected, but it did not include every person affected. This was amended in 2001. However, one woman who had no descendants working on her behalf, Elizabeth Johnson, Jr., was accidently left out. During the 2020-2021 school year, 8th grade students from North Andover, Massachusetts decided to take up Johnson’s case. The students researched how to pardon Johnson and began working with a state senator. The students read Johnson’s trial testimony, wrote a bill to pardon her, and sent letters to legislators. Their work paid off in March 2021, when Bill 1016 was introduced. It is still being heard by the legislature.

One of the early European efforts to correct the record began in 1982 when Walter Hauser, a lawyer and journalist, sought to exonerate Swiss woman, Anna Göldi, one of the last to be killed for witchcraft in 1782. In 2007, he produced evidence that her trial was illegal, thereby clearing her name. Since the early 2000s in Germany, descendants have worked to clear their ancestors’ names. Other people without personal ties to the accused are motivated by memorials that mark where accused witches were punished. They argue that such memorials spread false history and do not acknowledge deliberate persecution of women.

Claire Mitchell, a lawyer in Scotland wants to combat the erasure of these women from history. Because of continued silence and stigma about the trials in Scotland, their stories are not part of the public conscious. Additionally, because so many people were affected in Europe, it has been difficult to track down all names and reconstruct what happened. In 2020, Mitchell started a group, “The Witches of Scotland,” to uncover and memorialize the estimated 4,000 forgotten witch-trial victims there. Mitchell is campaigning to posthumously pardon all names they can gather, solicit an official apology, and create a national memorial. So far, she has unveiled a plaque commemorating 380 women and is constructing a legal argument to take to the government. Those who are seeking historical justice for accused witches argue that although the wrongs of the past cannot be undone, the history of what happened–and who it happened to–can be accurately remembered.